Body Capacity: A Trait to Remember

Often production characteristics are overlooked in exhibition birds, which is to the detriment of the flock. Productivity, livability and fertility are all tightly coupled and when you lose one, you tend to lose them all. One measure of a good, productive bird is abdominal body capacity. Birds with good body capacity have the abdominal capacity to convert food into flesh and/or eggs.

Of course you need to take the breed’s individual optimum physique into account when assessing your birds. You want good body capacity on both your Leghorns and your Cornish but you would not expect them to be the same. Rather you would look at the capacity as compared to type and conformation. We’ve all seen those Leghorns that are so narrow they produce undersized eggs or those Cornish that are so wide as to be unable to mate.

An indicator of good abdominal capacity is a bird’s width between the legs, while considering the breed’s ideal width. Birds with narrow bodies don’t have the optimum room for their internal organs to function at peak efficiency.

When I’m at poultry shows, another fault that I see on a regular basis is lack of good leg structure. It seems that breeders pay attention to color and type well enough. However, it seems some folks forget to look any lower than a bird’s keel bone when selecting breeders.

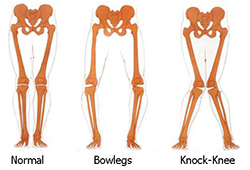

A chicken’s legs should be straight when viewed from the front. I’m seeing birds who are either knock kneed (cow hocked) or bow legged (curved outward). Remember, a bird with leg issues will not be able to move naturally and can develop leg problems later in life. I’ve attached an illustration of knock kneed and bow legged conditions so you can see what they look like. When you’re next evaluating birds for potential breeders, give the legs the attention they deserve. You’ll produce better birds when you do.

By Rip Stalvey