Common Poultry Lice

This article on common poultry lice is an excerpt from the Small Flock Poultry Health Manual published by the Province of B.C. Ministry of Agriculture. The full manual can be accessed by clicking here.

Lice are small (most between 1 to 6 mm in length), wingless, straw colored insects with a somewhat flattened appearance and a generally elongated abdomen (last body segment). All poultry lice have chewing mouthparts and feed on dry skin scales, scab tissue, feather parts, and can feed on blood when skin or feather quills are punctured. Lice are commonly found on both the skin and feathers and can move from one bird to another when birds are kept in close contact. Eggs (nits) are usually attached to the feathers. Lice are ectoparasites and spend their entire life on an animal host. Lice are generally host specific, meaning that they can feed on only one or a few closely related species of animal host. Poultry lice cannot survive on humans or on our domestic pets. In fact, poultry lice will generally complete their entire life cycle from egg to adult on a single bird, and will die in a few days to a week if separated from their host. Lice numbers on poultry tend to be greatest during the autumn and winter.

Poultry lice are not known to transmit any avian pathogens, although some wild bird lice are suspected of transmitting pathogens to their hosts. Parasitism with lice frequently accompanies poor health due to other causes, and is especially harmful to young birds in which high numbers of lice may cause sleep disruption. Effective host self grooming is an important means of reducing lice. Lice populations are generally higher on birds with beak injuries or on those that have had their beaks trimmed. Molting greatly reduces lice populations and severe problems with lice can be reduced through forced molting and rapid removal of egg laden feathers from the facility.

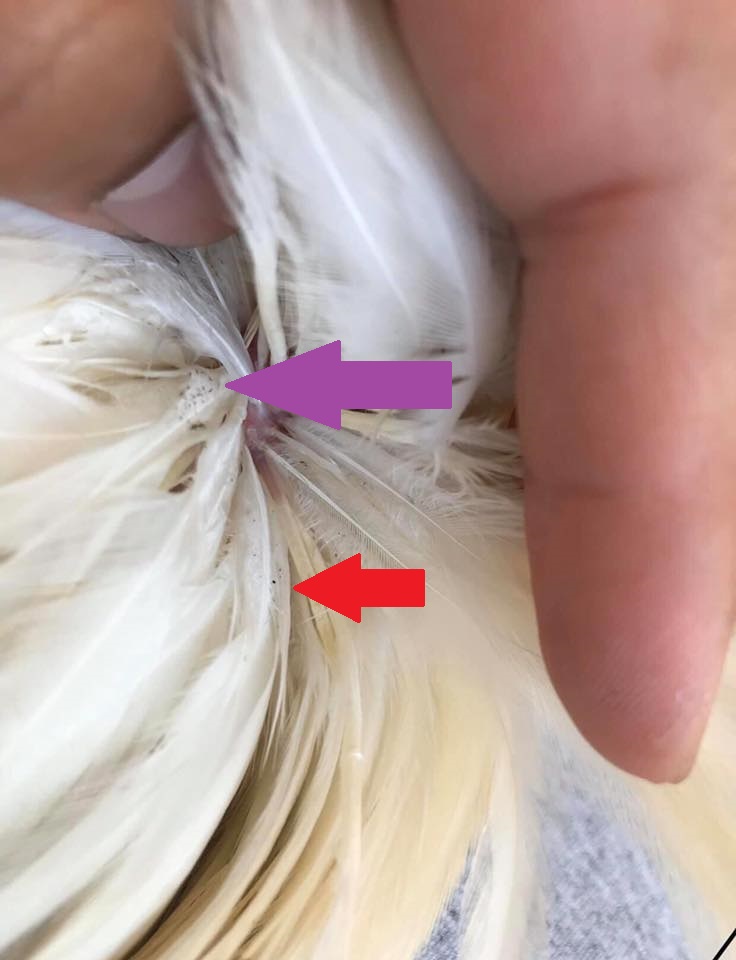

The two most common species of lice affecting California poultry are the chicken body louse (Menacanthus stramineus) and the shaft louse (Menapon gallinae). Adult chicken body lice measure 3-3.5 mm in length while adult shaft lice measure about 2 mm in length. Adult chicken body lice are most prevalent around the sparsely feathered vent, breast, and thigh regions. Eggs of the chicken body louse are cemented in clusters to the base of feathers especially around the vent, while eggs of the shaft louse are cemented individually at the base of the feather shaft or along the feather barb in the breast and thigh regions. Eggs of both species require 4-7 days to hatch and then 10-15 days to become adult lice. Adult lice can lay from 50-300 eggs in their 3 week lifespan.

Birds should be examined for lice at least twice per month. Examination for lice involves spreading the feathers in the vent, breast, and thigh region to look for egg clusters or feeding adults at the base of the feathers. The presence of a few lice per bird, or the presence of egg clusters indicates the need for treatment. Chemical treatment, if required, should be performed at 10 to 14 day intervals until control is achieved. Lice eggs are resistant to insecticides, so a single insecticide treatment may fail to provide control as lice protected within their egg shell will hatch after the insecticide is no longer active. By treating at 7-10 day intervals, the generation of lice that survived the previous chemical treatment while in the protected egg stage will be killed by the subsequent treatment before they are able to lay additional eggs.

Written by:

Brigid McCrea, Graduate Research Assistant, Poultry Science Department, Auburn University

Joan S. Jeffrey, former Extension Poultry Veterinarian, University of California at Davis

Ralph A. Ernst, Extension Poultry Specialist, University of California at Davis

Alec C. Gerry, Assistant Veterinary Entomologist and Extension Specialist, University of California at Riverside