Henry Lee: Poultry Artist

Below you can find several accounts on the legacy Mr. J. Henry Lee created during his time as a poultry artist.

Mr. H. S. Babcock’s Accounts on Henry Lee:

I am glad of the opportunity afforded me by the Editor of the Reliable Poultry Journal, of expressing some of my impressions of the late Henry Lee, at one time the foremost poultry artist in this country.

Mr. Lee was of medium height and slender build. His features were delicately molded. His complexion was pale and seemed even whiter than it was in contrast with his dark hair. His hands were rather small and the fingers long and tapering. The ruddy glow of sturdy health was not his, but his eyes shone with the fire of an unquenchable spirit. Had he been a woman the word “spirituelle” would have been properly descriptive of his appearance. But he was not effeminate; on the contrary, he was a manly man.

Mr. Lee was of medium height and slender build. His features were delicately molded. His complexion was pale and seemed even whiter than it was in contrast with his dark hair. His hands were rather small and the fingers long and tapering. The ruddy glow of sturdy health was not his, but his eyes shone with the fire of an unquenchable spirit. Had he been a woman the word “spirituelle” would have been properly descriptive of his appearance. But he was not effeminate; on the contrary, he was a manly man.

J. Henry Lee was one of the purest minded men I ever knew. There was nothing in his nature to which coarseness responded. His lips uttered no questionable expressions and his mind conceived no unclean ideas. If an evil desire over lurked in his heart, it never was allowed to escape from its prison. So far as one could judge from association with him, he need never to have blushed for his most vagrant emotion or wandering thought.

But while thus delicately constituted, while instinctively shrinking from evil, J. Henry Lee was a man who dared to combat falsity and who could be aggressive in the cause of truth. In contending for the true and against the false “he had the strength of ten, because his heart was pure.” Where a moral question was involved, the manly spirit of J. Henry Lee towered in strength over his physical weakness and proved him to be a man among men.

FOREMOST ARTIST OF HIS DAY

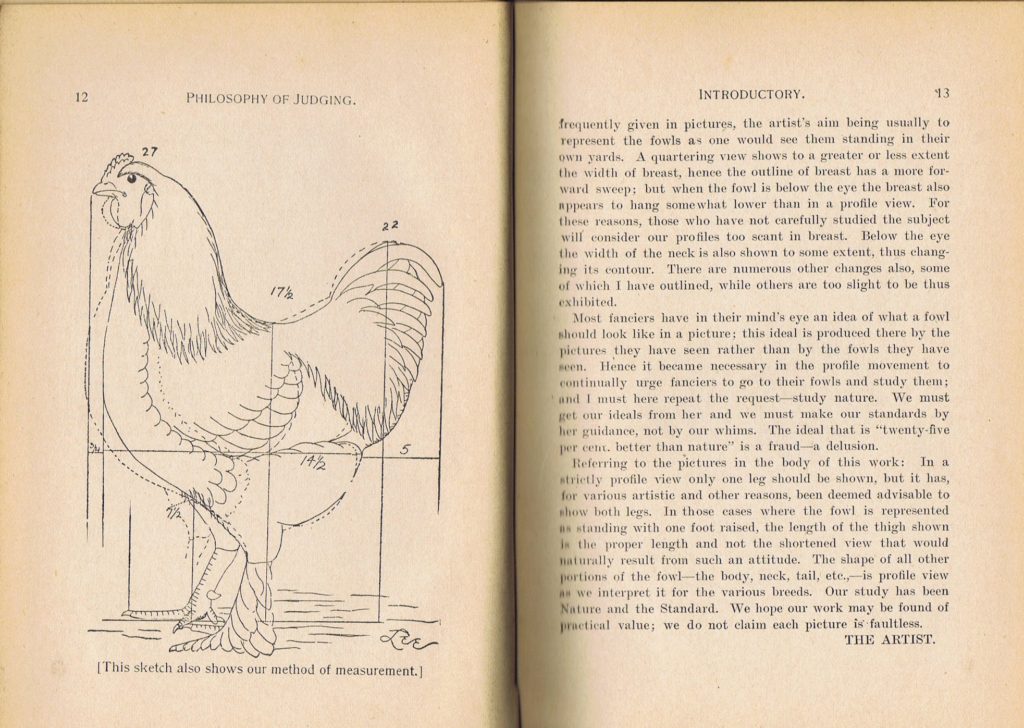

As a poultry artist he, in his day, was undoubtedly in the front rank. No man of that time could interpret better than he the requirements of a Standard in pictorial terms. And because of this ability he was engaged to illustrate “The Philosophy of Judging“ and to produce most of the profiles in the American Standard that was later marked “obsolete.” Those profiles, though finally rejected, were nevertheless valuable to the poultry fraternity, because, despite the criticisms urged against them, they really depicted the flat profile view of the various breeds, and especially because they rendered possible the production of an illustrated Standard. Those profiles taught poultry people to demand and to obtain something more than a mere word description 0f the various breeds of poultry. And it is to be hoped that the progress thus begun will not stop until the American Poultry Association has a Standard illustrated in colors. This was the end some of us had in view when we secured the insertion of those profiles in the now “obsolete” Standard. We advocated what is now the ideal, but we were willing to take what we could get, until the time was ripe for something better.

J. Henry Lee’s work was done conscientiously. The mechanical part of it was almost perfection. Every detail was finished with great care. Nothing was too small to be wrought out carefully. Indeed he never seemed to consider the relative importance of parts of his work, but deemed it all worthy of the most painstaking care.

No doubt Mr. Lee had his limitations. There was something mechanical and mathematical about his work. While this rendered him an accurate delineator of fowls and a superb interpreter of standard requirements, it nevertheless prevented him from becoming a great artist. His pictures lacked in some degree “the light that never was on land or sea.” They are accurate, even noble, representations of fowls as they were in actual life, but they are not flooded by the sunlight of imagination. Note his crude attempts at landscapes and contrast them with the excellence of his illustrations of the fowls! As pictures, prized for the appeal they make to the love for the beautiful, the illustrations made by Mr. Lee do not approach those of some of the leading poultry artists of today, especially of the one who stands foremost among his brethren, Franklane Sewell. Yet Lee’s pictures have, and will continue to have, a value for the real student of the development of the poultry interests of America. Those pictures taught the public much about the beauty and value of thoroughbred poultry; they stimulated the desire for more and better fowls; they recorded, with an accuracy unsurpassed, the development that through bred poultry had made in his day, and I believe they helped to produce better artists than we had up to that time. The American public, especially that part of it interested in thoroughbred poultry, owns an unpayable debt to the noble and incorruptible man and the thorough and accurate poultry artist, J. Henry Lee.

HIS WORK OF PERMANENT VALUE

One thing more, perhaps, should be said. Mr. Lee was a young man when he died. His work was constantly improving during his life. Perhaps if he had lived the allotted span of life, his art might have escaped from the trammels by which it was bound; it might have over leaped the mathematical and mechanical barriers, and Mr. Lee, giving full play to a chaste and cultivated imagination, might have produced illustrations that would prove “a thing of beauty” and “a joy forever.”

But whether this would have been so or not, to the student of poultry the work of J. Henry Lee can never cease to have value. As an illustration of this, let one examine almost any of the cuts in “Philosophy of Judging,” particularly the cut of the Light Brahma male, the Barred Plymouth R0ck or the Black-breasted Red Game, and see how faithfully they reproduce, in pictorial terms, the descriptions of the text. These cuts are not to be compared with other cuts of the same varieties made in recent years, nor to be criticized by comparison with personal ideals, but are to be studied as interpretations of the text and of the standards then existing. Moreover, they are to be studied in their true positions, as profiles, and not as the more common three-quarters view, which produces more attractive pictures. Studied in this way they will be seen to be of great value even in the interpretation of the latest Standard. The profile view is not the most attractive view of a fowl, but it is essential that it be considered by the poultry judge in arriving at a correct estimate of the score of a fowl. In making these cuts Mr. Lee kept all these purposes steadily in view and his work was a real triumph in interpretation.

When such men pass from the scene of their earthly labors their associates suffer a great loss. They miss the kindly presence, the cheerful voice, the glad companionship. But, they really do not lose their friend. The artist can say as said Horace of old, “I shall not wholly die.” He lives in his works, and because his works are the sincere expression of his best moods and highest ideals, the better part of him is not even temporarily lost. I miss J. Henry Lee. He was a friend whom I felt I could ill spare. But I am thankful that though he is gone, his works remain and they serve to recall a talented artist and one of the best and truest men that ever lived.

Mr. I. K. Fletch’s Remarks:

I fully endorse what Mr. Babcock has written in regard to J. Henry Lee. I regret that I have no special cuts of his that l deem of extra merit to present here. His patrons greatly appreciated his willingness to present in his pictures their thoughts and ideas, sacrificing his own individuality and confining himself to the mechanical part of his work. We should remember that those were the days of wood cuts. As an illustration of this I refer to the cut of “Main-spring” the Light Brahma cock in “Philosophy of Judging.” It is the composite of the measurements by me of more than twenty good Brahmas of the times.

This book was conceived by me after the meeting at Buffalo that repudiated the efforts at Indianapolis the previous your to secure side profiles in the Standard of 1883. You know how tenaciously I have adhered to the side profiles in Brahmas.

Mr. Lee knew that I objected to the plan even then advocated of making imaginary pictures on the plea that we should then have something beyond nature to work up to. My idea was then (and I still adhere to it) that the illustrations should be faithful representations of nature’s best, not the creation of man’s imagination. Mr. Lee tried to give us an idea of the plumage as it was massed on the fowl. He agreed with me that the delineation of individual feathers was too often misleading as to the appearance of the fowls themselves.

One thing that makes it hard to write of the work of Mr. Lee is that for a long time his output was owned by the paper with which he was connected. The pictures by which we must judge of his growing excellence are those which he produced in the few years during which he worked under his own name.

In his day the work of the poultry artists was controlled, as I have said before, largely by the patrons’ ideas and consequently we see a marked difference in the shape of different outlines of the same breed, though drawn by the same artist, but he was the pioneer among poultry illustrators, and they, as well as the poultry fraternity, owe him a great debt.

Further Remarks from Mr. H. S. Babcock

A letter from W. D. Page, publisher of ” The Philosophy of Judging,” a few days ago contained the sad intelligence that J. Henry Lee, after a long illness, died at his home in Indianapolis, Ind., March 5, 1895.

We — this includes the whole fraternity — have lost a friend; one who was true and loyal in every position in life; a loving and lovable son and brother; one who commanded the respect and esteem of all with whom he came in contact, either socially or in a business way. We voice the sentiment of every reader of the Monthly when we tender the mourning family our deepest, heartfelt sympathy. From a letter from the sister of Mr. Lee we learn the following facts concerning his life and illness:

He was born in Otter Creek Township, Indiana, June 24, 1861. The family moved to Indianapolis in 1874. He was never married, but lived at home with his father, mother, brother and sister. He was a member of the I.O.O.F. eight years, and was a Past Grand at the time of his death. He had been an engraver of poultry and stock cuts for ten years.

His health began to fail about five years ago; for several months before his death he was unable to attend to any business whatever; he was always cheerful and planning for the future, “when he would get well.” He was conscious up to within five hours of his death.

The writer never had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Lee, but for several years we have had almost constant business relations and we came to regard him as a personal friend, one whom we could trust implicitly and unreservedly. As an artist, in his particular line, he easily stood at the head of our wood engravers. We do not know where to look for one competent and skillful enough to take up his work. His name will live, after many of ours will be forgotten, in his fine engravings; they are his enduring monument.

In a very recent letter from his sister, accompanying the portrait which accompanies this notice, she wishes us to say that she is very grateful for the many kind words of sympathy and expressions of regret which have been received by her self and parents from Mr. Lee’s many friends.

Others, perhaps, knew Mr. Lee more intimately than I; but I had met him at various meetings of the A. P. A , and as he was the illustrator of “The Philosophy of Judging,” I was brought into frequent correspondence with him. I knew him well enough to know that, in his death, the poultry fraternity has lost a valuable member and I a personal friend.

Mr. Lee was best known as a poultry artist. His illustrations, mostly ideals, for during his active years ideals were all most solely demanded, were finished with an accuracy that no poultry artist has surpassed. He seemed to catch at a glance the absolute perfection of a variety and be able to fix it with the graver to teach us what, at its best, it should be. The cuts in “The Philosophy of Judging” are good examples of this kind of work, especially those of the Light Brahma, the Barred Plymouth Rock male, White Wyandotte and Black-breasted red Game. But all his illustrations were not ideals, and the portraits which he produced give an indication of what he might have done in this line of work if his life and health had been spared.

Mr. Lee was best known as a poultry artist. His illustrations, mostly ideals, for during his active years ideals were all most solely demanded, were finished with an accuracy that no poultry artist has surpassed. He seemed to catch at a glance the absolute perfection of a variety and be able to fix it with the graver to teach us what, at its best, it should be. The cuts in “The Philosophy of Judging” are good examples of this kind of work, especially those of the Light Brahma, the Barred Plymouth Rock male, White Wyandotte and Black-breasted red Game. But all his illustrations were not ideals, and the portraits which he produced give an indication of what he might have done in this line of work if his life and health had been spared.

As a frequent contributor to the poultry press and the author of ” Some of Lee’s Ideas,” he showed himself to be the possessor of a clean English style that made his ideas easily understood by every reader. And these ideas were well worth understanding, even if, instead of being laid bare by the lucidity of his language, we had been obliged to dig for them as for hidden treasures.

But it is as a man that I care the most to speak of J. Henry Lee. He was a manly man. In all the relations of life, as son, brother, friend and neighbor. He was faithful to every obligation and duty. He was honest, pure-minded, and clean in every way. What was pure and what of good report were the things his mind dwelt upon. No man ever conversed with him without the feeling of cleanness, mental and moral, as the result of such conversation. Although smitten with the fatal disease five years ago, he labored until the end with a rare degree of cheerfulness. Few of us can look death in the face with the courage that this modest, retiring friend of ours did. He might have said, in the words of St. Paul: “I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith; henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous Judge, shall give me at that day.”