Calls and East Indies: What You Should Know Before You Buy

This article on what you should know before you buy calls and east indies is being republished from Acorn Hollow Bantams website with permission from Lou Horton.

I began raising Calls and Black East Indies in 1970. Back then, the classes at shows were modest in size and really good birds were few and far between. If one had one or two really good birds, one could count on winning at most shows even if those birds were not in good condition when they were shown. Today, very good birds are in the hands of many breeders and exhibitors and the bantam duck classes at many shows are so large and competitive that a bird must usually be in excellent condition to win. The relative quality of top birds are also much better today than it was thirty years ago. Furthermore, the judge is often confronted with a number of very good birds with slightly different strengths. Some judges are very particular about the fine points of body type and will make those criteria the most important when placing the birds. Others will make color a major consideration; particularly in placing classes of parti colored Calls such as the Grays. Still others (often the less experienced) will make small size a major criteria; even at the expense of good Call type. What I am trying to say is that winning is no sure thing today even with fine quality birds.

Because some judges put a high priority on very small size, it may be tempting to use very small birds in the breeding pen. That would usually be a mistake. While there are exceptions, very small Calls usually make poor breeders because the small males may well be unable to breed due to their short legs and very small females often lay no eggs or very few eggs. Such birds also often tend to be less vigorous and therefore more delicate. A breeding line built with such birds would likely be doomed to extinction within a few years. The ideal is to use a medium sized bird strong in the fine points of type and (in colored varieties) possessed of sound color. This type is what I attempt to provide my customers when I sell show quality birds. Such birds are not only useful in the showroom but are also useful as breeders. The Standard of Perfection writers realized that they were part of the problem because of the “smaller, the better” wording which had been inserted in the standards many decades earlier when most Calls were too big. They have since removed such wording from the standards and have assigned ideal weights to the bantam ducks as they have to all of the other bantams.

The Gray and White Calls are far more established than the other varieties. In fact, they have been bred for well more than one hundred years while the oldest of the other varieties are less than thirty years old. The newer varieties are, therefore, almost always less refined in type and color and are usually somewhat larger in size (drakes especially) than well bred Grays and Whites. If one is looking to “go to the head of the Call class” at the shows, therefore, it is probably unwise to take up the Snowys, Pastels, Butterscotch, etc. If, however, one enjoys the often striking colors displayed by these varieties and would welcome the challenge of helping to perfect them, then they are a good choice. Also, while we are on the subject of the newer varieties, be aware that the two “blue” varieties (the Blue and the Blue Fawn) do not breed 100% true. Because the blue color gene is recessive, Blues will produce some blacks and some silvers and Blue Fawns will throw some Pastels and some Grays. Just so you know. I try to take the relative quality of the birds into consideration when I price my birds. That is why the best quality I offer in the newer varieties is priced comparably to the breeder quality Whites and Grays.

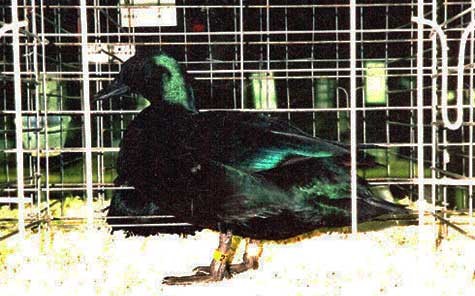

Even as recently as 15 years ago, it was common to see classes of Black East Indies which contained many birds which approached 3 lbs. in weight. Furthermore, many were poorly colored. Until the late 1980’s, it was almost unheard of for an East Indie to be named Champion or Reserve Champion Bantam Duck when Calls of decent quality were present. Today, East Indies routinely hold their own against the best Calls in the world. There are, however, problems which come with the desire to produce brilliantly colored birds which have black bills, legs and feet. East Indies share with the other black breed of duck (the Cayuga) the tendency for white to begin showing up in the plumage of the most well colored specimens relatively early in their lives. The problem is especially noted in females that can have a significant amount of white in their plumage by 2-3 years of age. They are still valuable as breeders; they just may not be good show birds at that point. Birds with a dull black finish to their plumage do not seem to show white in their plumage as early as those with a high degree of metallic sheen to their plumage.

The other major problem in black ducks is a tendency for the black pigment in the bill, legs and feet to fade as the bird ages. A bird with excellent black in those areas as a young bird may begin to show hints of olive in the bill and/or an orange cast to the legs and feet as it ages. The standard writers recognized that this is part of the natural aging process in black breeds and specifically allow for it in their comments about common defects. I try to combat the loss of black pigment by breeding from males that have retained good bill and leg color at several years of age but nobody can predict how much pigment color a bird will lose (if any) from year to year.

My purpose in writing this article is to let prospective Call and East Indies buyers know about problems that they will face and to help them form realistic expectations. Whether you purchase any calls or east indies from me or not, I want your experience with bantam ducks to be a positive one.

By Lou Horton