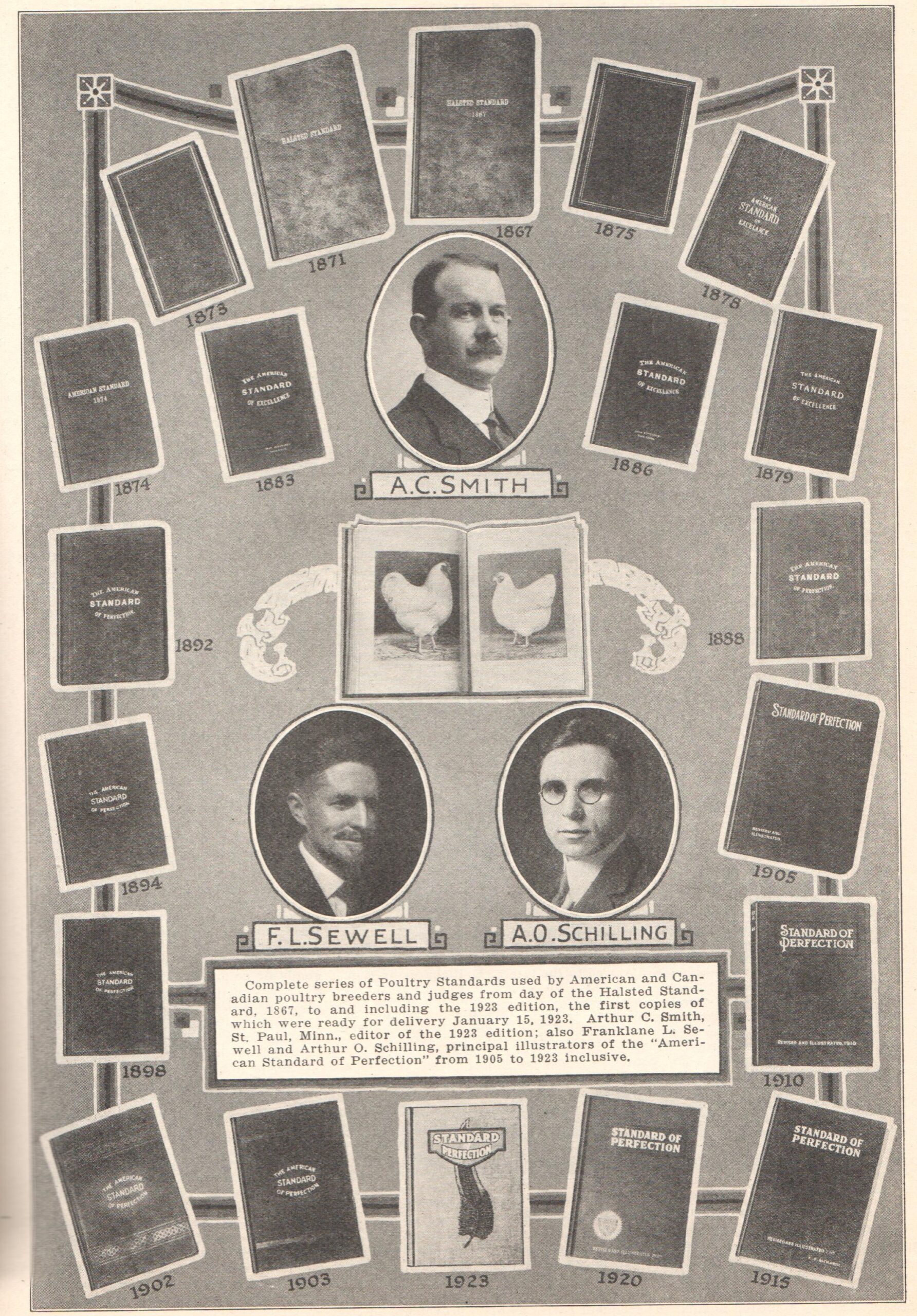

The Great Poultry Artists

The American Poultry Association has never had a staff artist to use for its artwork. When illustrations were needed, the committee in charge of the Standard of Perfection would request bids for the work from the leading great poultry artists of the time.

Many of the leading artists of the day were employed by major poultry magazines such as Farm and Poultry, American Poultry World, Reliable Poultry Journal, etc. For this reason a given Standard of Perfection will have multiple artist’s work represented in that edition.

We have attempted to include information on all of the Standard artists and continue to search for information to flesh out the pages. If you note any omissions or errors please notify us.

Below are two articles that deal with a change in the poultry artist’s world. This became the end of the era for drawing poultry and retouching pictures towards the idealized Standard-bred birds. As photography became cheaper, real specimens were preferred over artwork, and thus ended the generation of the great poultry artists.

The Ascendancy of Art

Bliss Carmen has written a book, “The Friendship of Art,” the philosophy of which I have greatly enjoyed. Nevertheless I have always been more or less skeptical about the place art, with a question mark after the word art, held in relation to the thorough or standard bred poultry industry. Much ink has been spilled over the question of having photographs taken and retouched by “artists” and others until it finally resolved itself into a hand-to-hand combat similar to the Mexican situation.

The knockers have been many. They have been loud in their demands that “chicken pictures should be taken just as they are and not faked a bit.” The poultry artists of this country have been working quietly on, never resenting the insinuations of an ignorant public, until finally one morning the poultry public awoke to the fact that it was the poultry artists of this country, the real truly great poultry artists of this country that were the ones that were really taking the pictures just as they were and presenting them to a critical public unfaked, and that the unknown and unheard of local photographer was the one that was doctoring up the poor pictures and really doing the faking.

While at the last Chicago show I got the final scales pulled off my eyes in this respect when I slipped back through the coop storage room to where the three S’s (Sewell, Schilling, and Stahmer) and one or two other artists were photographing the birds. I had always been of an inquisitive frame of mind, and here now, thought I, will I quietly get onto some of the “tricks of the trade.” Soon I not only became interested, but I became absorbed. I found them photographing at 9 o’clock in the morning, and here it was 3 in the afternoon before I realized it was past lunch hour. I learned what some of the “tricks of the trade” were all right, but I found they were not what I thought of finding.

The men engaged in the poultry industry in this country, beginning at boyhood and sticking to their knitting straight along for a score or more of years, are far and few between. Most of them have taken it up as a fad some time or other and gradually drifted into it.

But here I found among the artists men who had spent a lifetime, every minute, every hour, studying and working to become more proficient in portraying fowls in lifelike poses. Men raising chickens can devote an hour or two a day to their fowls and get fair results, but here were men so deeply engrossed in their work that it necessarily consumed them until it took every minute of their time; had taken some of them to Europe in their quest of knowledge, regardless of finances, until, as Mr. Sewell related, on his return the first time he barely had enough to bring him back. This is fire kind of stuff these men are made of. They have staked their all in perfecting themselves to portray fowls. This is the difference between an artist and an artisan. The artist stakes his all and works for the pleasure of working, while the artisan works to profit by his labors, regardless of results.

I found Mr. Sewell and Schilling taking photos side by side in a little noisy room where the birds were being attracted every minute by the dozens of street cars passing as they can only pass in Chicago. A bird would be brought in, flopping and cackling in a hysterical way, but in a minute or two the most nervous bird in the hands of these gentlemen would be as quiet as if in a sleep.

I found Mr. Sewell and Schilling taking photos side by side in a little noisy room where the birds were being attracted every minute by the dozens of street cars passing as they can only pass in Chicago. A bird would be brought in, flopping and cackling in a hysterical way, but in a minute or two the most nervous bird in the hands of these gentlemen would be as quiet as if in a sleep.

Patience and kindness are personified in these poultry artists and this I found to be one of the tricks, but so legitimate that few of the laymen would care to use them. It was a gentle rub and a br-r-r-r and a biz-z-z-z and a tickle – under the throat and a pat on the back, but never a quick or excitable move that made these works of art a reality.

It was amusing to see and hear the performance of Louis Stahmer and A. C. Hawkins. I came up and heard them fussing in this friendly fashion:

A. C. H.——“Aw go on away, Stahmer and let me pose a bird once. You know you never got a picture of one of my birds as good as the bird really was in your life. Stand back there, Louie, I say, and you snap the picture when I pose the bird. I’ll show you how a Barred Rock really ought to look.”

L. S.-—-“Well, Mr. Hawkins, pose the bird yourself once.”

A. C. H.—“Snap him, Louie. Snap him I say. Now why didn’t you snap him when I said?”

L. S.—“Why, that wouldn’t make a picture worth looking at.”

And so it went back and forth for some little time and the poses Mr. Hawkins, the veteran Barred Rock man, the past master at training birds to pose in their coops, got more amusing and frightful to behold. Mr. Hawkins was insistent for some time that he could pose a bird as good as any d— artist, but it wasn‘t but a few more minutes until he saw his folly and gave up in disgust with the frank admission:

“Well, do it yourself, Stahmer; that is what you are paid for.”

With that Mr. Stahmer took the excited bird and in quicker time than I can write it had him in poses the like I had never beheld before and that I had always thought impossible and faked. It was all in knowing how.

These portrayers of bird as they are are so faithful to their trust of getting the best there is in the bird out that the way they waste exposures is a “fright to behold,” in everyday par lance. With their loaded film packs they keep on pulling out and snapping and snapping and snapping on the same bird for as high as a dozen exposures. Generally the second or third exposure would be A-No. 1, but they are not content, and all unmindful of the high cost of living and the kodak trust, keep making exposures by the dozen until after two days’ work the floor where these men had worked was thick and deep with these little black slips of paper, 5 by 7 inches, each one representing an exposure.

The rapidity, patience and quietness of their work was amazing. Mr. Harrison was having a number of birds photographed—a dozen or more, I should judge. Just as fast as a man was bringing them up Mr. Schilling was taking a half dozen to a dozen exposures of these Red pullets. Said I to Mr. Schilling:

“Don’t you keep a note book and number these exposures and put down the leg band numbers so you can tell one bird from another! I would think after developing several of the same bird and eight or ten birds’ pictures at the same time you would get confused.”

I had taken into account how I could tell all my birds apart and thought I was quite smart in stating to visitors that I could tell every bird on the place like an acquaintance but I could not see how those artists could tell one bird from another when taking several pictures of the same bird and a number of birds just alike and never seeing the bird but for a few minutes while photographing them.

Mr. Schilling gave a story as an example in answer to my question. He stated he identified a bird after photographing it five or six years back and that he never forgot a bird after once photographing it. This I deem very remarkable to say the least.

After watching the January and February poultry journals I was more convinced than ever that the real poultry artists of this country were being grossly mistreated in being criticized as they have in the past. Here they were in the January and February numbers— pictures that I had seen taken and every feather just as it was taken. There was the identical bunch of dried flower stocks that Stahmer had picked up in a corner of the Coliseum from some flower show to make the photo realistic and in every one of these Chicago photos could be seen the dried up flowers that made the photo look like it had been taken in a fence corner somewhere miles away from the city. I was convinced beyond a doubt and forever after will I champion the cause of the men who are devoting their lives to faithfully portraying the best that are in our fowls. To be convinced yourself turn back to January and February numbers of American and note how many Chicago winning birds have that same background. Mr. Stahmer, being in his home city, with opportunity to develop his work rapidly had these same pictures showing them about the show room in a few hours after they were taken. The proof of the pudding is in the eating and many of the boys at Chicago, like myself, shrugged their shoulders and gave up and were convinced that it was in the know how in taking rather than doctoring afterwards, for here Mr. Stahmer was showing a dozen or more taken the day before and which it was a physical impossibility to retouch all before he brought them back to the show room, perfect, for our inspection.

By H. V. Tormohlen. Portland, Ind. (taken from American Poultry Journal April 1914)

Unretouched Poultry Portraits by the Great Poultry Artists

Unretouched Poultry Portraits by the Great Poultry Artists

During the year to come American Poultry Journal intends to specialize in unretouched portraits of Standard-bred poultry. Our artist, L. A. Stahmer, has proved beyond doubt that beautiful and artistic illustrations can be made from actual portraits of thoroughbred fowl with no need for retouching.

Fowls can be pictured exactly as they are without any faking of the picture, and the illustration can do justice to the fowl, the variety and prove a credit to the breeder. Mr. Stahmer has been making fine pictures of some of the best Standard-bred birds produced in this country, that show the birds just as they are. The portraits are portraits and not idealized pictures that show the artist’s skill in faking and retouching.

The very best pictures of real fowl that can be made will be used exclusively in American Poultry Journal this coming season. If you want to see what the show winners actually look like when on exhibition you will find what you want in A. P. J. illustrations.

At the present time much effort is being given toward securing the truth in advertising. We believe in and desire to encourage the truth in advertising and truthful advertisers. We believe that readers everywhere will welcome truthful portraits of thoroughbred poultry. Whenever you see under an illustration in A. P. J. the legendary “Engraving made from unretouched photograph A. P. J.” you can feel certain that you are seeing a faithful representation of the bird as it actually is. We believe that the day of the retouched, faked and skillfully idealized poultry portraits has gone by and that fanciers everywhere will welcome truthful pictures. The place for idealized pictures of poultry is in the Standard where the fancier is given the portrait of an imaginary or supposedly ideal, 100 percent perfect bird as a pattern to work by.

If you want the best truthful portraits of real birds just as they are you will find them in American Poultry Journal this coming season.

By H. V. Tormohlen. Portland, Ind. (September, 1914)