The 1923 Standard of Perfection

Republishing of an article by Arthur C. Smith on the 1923 Standard of Perfection

Unquestionably, the new Standard will be more eagerly sought and more generally sold than any of the preceding editions. This will not be due merely to two most obvious facts: specifically, that more people in the United States and Canada are engaged in raising Standard-bred poultry and more recruits are entering the ranks than ever before, but also because the science and practice of breeding poultry has advanced during the past eight years and the new Standard records not only that advance, but is in a measure a vision of the future, by some of the best minds engaged in poultry work.

Each Standard seems to be perfect, or nearly so, at the time it is published, or at least breeders frame a description of their favorite variety which to them embodies all that is ideal. They neither can imagine nor visualize anything more perfect; yet, within half a decade or so, the ideal so recently perfect is found faulty in many particulars and the Standard is denounced as away behind the breeders and their birds. That was one of the criticisms of the Standard just passing, made by a certain few. In the future, my dear breeders and editors (some of you) do not forget that the Revision Committee of 1923 tried to make the Standard requirements sufficiently high to keep the breeders busy improving their fowls for eight years to come, or during the life of the present Standard. This committee was criticized on the floor at the last convention of the American Poultry Association for adopting descriptions too far in advance of the breeders and their birds, and, curiously enough, by some of the parties that not long ago proclaimed the present Standard “obsolete” and “behind the breeders.”

It will be of interest to you, reader, to learn whether the requirements of the new Standard of 1923 are likely to over-tax your skill as a breeder of the varieties you breed or favor. Of course, there are changes in the text. That is what “revision” is for. As progress in breeding is made ideals change. This simple fact conclusively proves that there are in reality no such things as ideals, unless we take the most perfect conceptions of our minds as our ideals in which case the ideals change and improve with the fuller development of our minds. An actual ideal, then, we never have in the sense of being actually perfect. Our ideal is but our mental conception at the time, and no mind is stationary. Therefore, Standards must change constantly and the Standard requirements should be as far ahead of the times as our minds can clearly vision, but not hazily imagine.

Each general revision marks, then, the beginning of a new epoch in ideals and hence in breeding, which epoch or which period is forecast for you by this new work, “The Standard of Perfection, 1923 Revision.” Its provisions indicate the goal of the breeder and exhibitor, and without it as a guide neither would have aims or objectives, the judge would be without authority and the industry without a purpose. Without this single guide a breeder cannot hope successfully to attain the highest accepted ideals or even approach them. Without the latest 1923 Standard, any breeder of Standard-bred poultry is absolutely out of the race for honors as such.

The above statements are as true in regard to judges of Standard-bred poultry as to breeders. No statement can be more obvious than that a judge must be exceedingly conversant with Standard requirements in order to meet with any success whatsoever in his chosen field.

The changes in text are many and varied. Many, here and there were made simply to express more clearly the meaning of the text, which is commendable. Others were made for the most fundamental of reasons, i.e., the characteristics of many breeds have changed or it was thought that they should change.

A great many, if not most of such changes, were adopted at the suggestion of the specialty clubs representing their respective varieties. This seems to be an admirable plan to correct an impression that is being created, perhaps for political effect, by certain agitators who are possibly more alarmed about votes than well-informed on actual conditions. To the end of informing readers generally as to the relations between representatives of the specialty clubs and the Revision Committee, I will state that there was ever a spirit of cooperation and a desire on the part of the latter to concede everything that could be conceded and yet maintain a consistent policy of Standard-making. In one case we were informed that the representative never saw the inside of a Standard and did not care whether we adopted his suggestions or not because if these suggestions were not adopted the club which he represented would print a Standard of its own. Even in this very extreme case, misunderstandings were found to exist, amicable relations were soon established, and adjustments that were not only satisfactory but very pleasing to all were adopted.

From the experience gained on three Revision Committees, and by working considerably on the fourth, I can say that while I believe that there is every reason to accord to specialty clubs every consideration possible and to weigh every suggested change most carefully and fully, yet, I can see great danger in accepting their words as final. One reason is that the younger and less experienced breeders are usually the most active and influential in circles of their clubs and their judgment is not always most sound. Many times they do not know intimately, as yet, the best interest of their own breed or variety, nor the limits of breeding possibilities. In the second place, they quite likely know next to nothing of the broad, fundamental principles of Standard-making, and are usually not a bit inclined to recognize them when pointed out. Their variety is their “supreme” and “sole” interest. In their minds, no others are worthy of much, if any, consideration.

As an example of the above, it is generally agreed that all Partridge varieties shall correspond in color description. But the recommendations of the Partridge Plymouth Rock Club might not and often does not correspond to those of the Partridge Wyandotte Club, and neither would conform to the recommendations from the breeders of Partridge Cochins; yet the avowed purpose of the Partridge Plymouth Rock or of the Partridge Wyandotte from the beginning until the present moment has admittedly been to place on the form of a Plymouth Rock or of a Wyandotte, the identical plumage of a Partridge Cochin.

The Specialty Clubs whose object it is to promote the welfare of Columbian Plymouth Rocks and Columbian Wyandottes did not recommend changes that are identical by any means; yet, the purpose of the creators of both these varieties was to acquire the Light Brahmas plumage. There must be some final agency to act as a clearing house between these specialty clubs in the interest of general welfare; if not, there will be very little uniformity in the Standard and without uniformity a Standard is a Standard in name only.

Changes in the arrangement of the text, which simplify the finding of disqualifications by placing them where they naturally belong, and the classification of general disqualifications and the rules on cutting for defects will appeal to those who are constant users of this book. A general index will be found in the back of the book, which arrangement permits a better grouping of the preliminary subject matter.

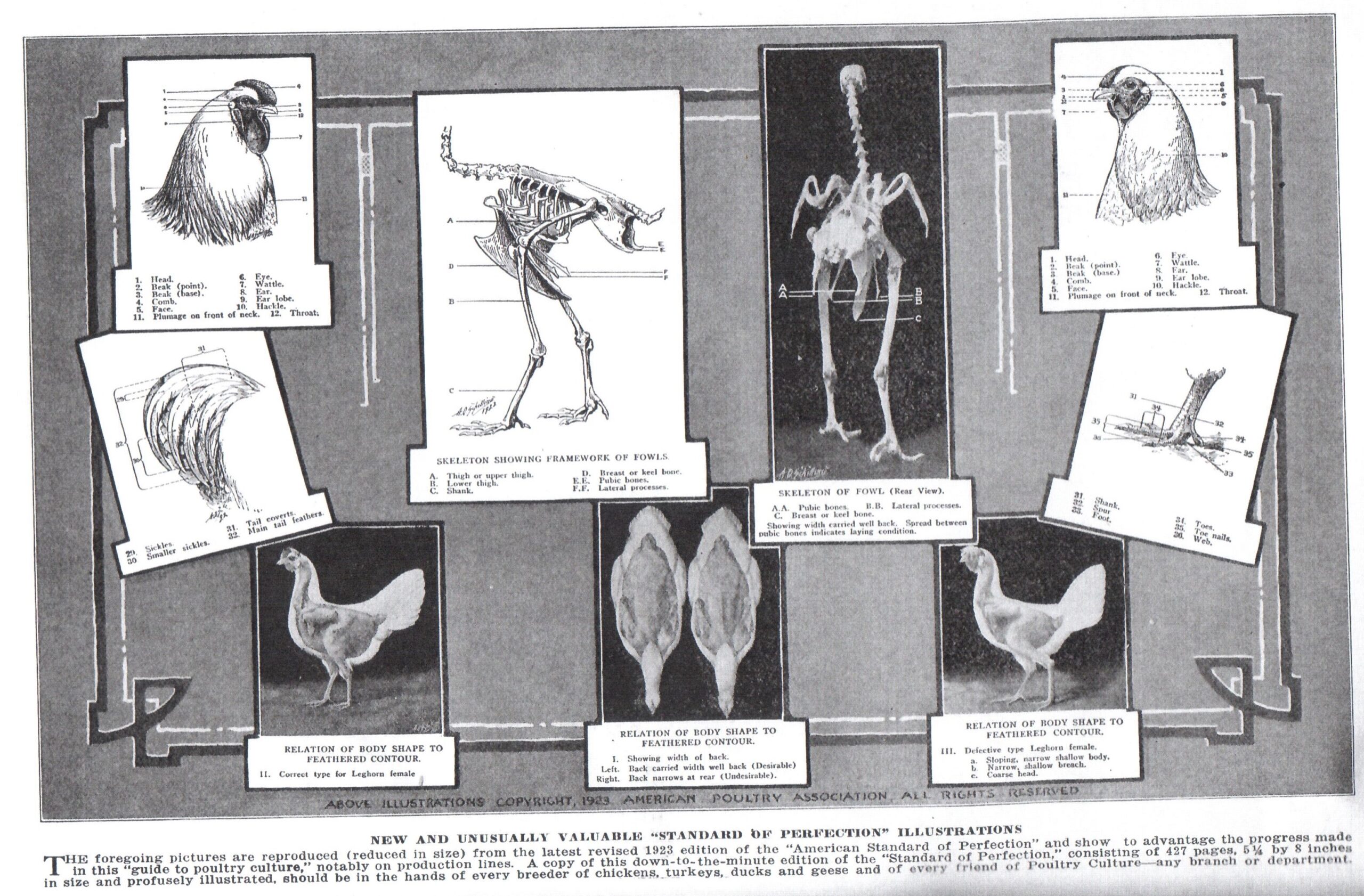

Another distinct benefit to the purchasers of the new Standards will come from a study of the new illustrations, of which there are many. They, too, have the advantage of uniformity. The old illustrations were to be prized in most every way, but they were the product of several artists, every one of them good, but of distinctive technique, which means that the different illustrations had a different tone or expression. This is very largely overcome by having all new cuts and changes made by one artist, the effect of such uniformity will improve the appearance of the book considerably.

Utility Features Receive Recognition in the 1923 Standard

The additional chapters constitute perhaps the most striking change, the most important of these deals with the market or utility side of Standard-bred poultry, though much more complete definitions are also found in the 1923 Standard. The chapter on capons which is an entirely new department, in reality admits market classes of all breeds to poultry shows, though only the heavy, or those of medium weight, are likely to take advantage of it. Interest in this feature has been shown at exhibitions already in advance of the Standard.

Another innovation is the chapter on “Judging Eggs.” This is introduced for the first time in any Standard and should do much to popularize egg displays in times which might well be characterized as “The Egg Age” in the Poultry History. At times it seems as though everyone was counting eggs and forgetting all about flesh, looks, and most everything else.

The text concerning market or utility characteristics of fowls has been both clarified and amplified by several new illustrations, and diagrams, and new illustrative charts by artist A. O. Schilling, showing a much more complete nomenclature have been added. These are new features and add much value to the book.

The utility features of poultry are thereby fully recognized and encouraged in the new Standard. We may say there are but two products from poultry, eggs and meat, and both are recognized and then invited to honorable places among our exhibits at all shows run under American Poultry Association rules.

By these additional features shows will be able to increase the interest felt in their exhibitions and will draw another and different class of exhibitors and visitors.

The Association has faith in this work, not only as a true and accurate description of what is or may be “best” in every way in the poultry world, but it has expectations so firm and so sound that they already amount to a realization of pecuniary reward that is most satisfactory to express this feeling mildly.

By Arthur C. Smith